Losing the Magic

🎥Creativity Film Club Vol 1: Kiki's Delivery Service, cycles of creativity, and the anti-magic of AI

Introducing: Creativity Film Club

You may have noticed that I like the movies. I only ever use my own photos my posts, and film stills when relevant (which is almost always). Movies are1 made by creative people, and there are so many that I think about on a daily basis in relation to creativity, and the experience of being an artist. This is the first installment of Creativity Film Club, a series dedicated to analyzing films from the perspective of a creative person.

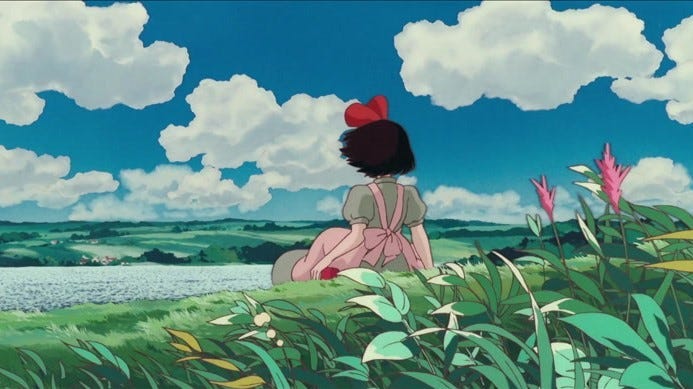

Creativity Film Club Volume I: Kiki’s Delivery Service

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) has long been one of my favorite movies. My mom bought the VHS on a whim, and it was my introduction into the magical worlds of Studio Ghibli: the Japanese animation studio known for producing enchanting, hand-drawn films. I constantly revisit the Kiki’s Delivery Service, a coming of age story that grows with you, only becoming more relevant with age.

This is Studio Ghibli (est. 1985) founding member, Hayao Miyazaki’s, fifth feature as a director, a story he adapted from a children’s novel by the same name, released in 1989. Just a few years later, after releasing Princess Mononoke in 1997, Miyazaki made his first announcement of retirement, declaring that he would step away from making features. Famously, he’s come out of retirement three times now, creating Spirited Away (2001), The Wind Rises (2013), and The Boy and the Heron (2023), (respectively), after each retirement announcement. What keeps Miyazaki coming back? Kiki’s Delivery Service, a relatively early installment in Miyazaki’s filmography, is a look inside the mind of an incomparable creative and how he operates.

To prepare for this analysis, I spent the past 2 weeks re-watching the movie, and all available documentaries on the subject of Hayao Miyazaki:

The Films:

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

The Kingdom of Dream and Madness (2013)

Never Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki (2016)

10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki (2019)

Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron (2024)

Of note is Never Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki (2016), which in my opinion, is essential viewing for understanding Miyazaki’s cycle of creativity.

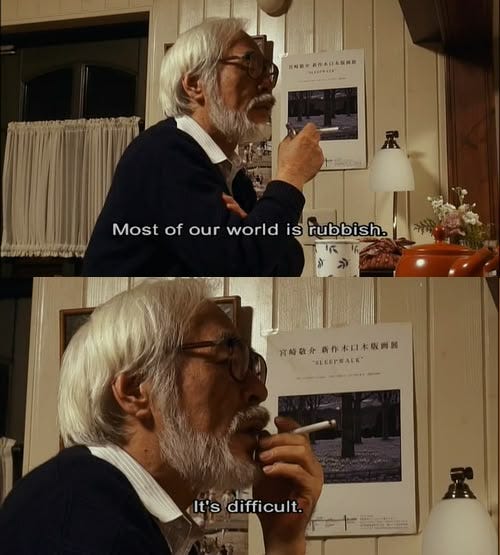

What begins as a documentary about Miyazaki’s foray into CGI for a short film, turns into a story about a return to form. In Never Ending Man, he approaches CGI animation for the first time, with trepidation, collaborating with young CGI animators to bring his caterpillar character (Boro) to life. His new coworkers chuckle at his detailed notes and directions. Frustrated, he hand draws the layout (animation plan) himself, and says something revelatory about his chosen medium:

“I think that CGI Animators focus on external movement, but ignore motivation. Movement isn’t neutral, it has intent. That’s what makes muscles move.” - Hayao Miyazaki, Never Ending Man (2016) (30:05)

It’s about 25 minutes later [in the film] that Miyazaki takes that meeting. Having dabbled with new technology, he agrees to hear about further developments in the realm of technology+animation. Stills from this particular scene have recently resurfaced and circulated, in which Miyazaki calls AI an “insult to life,” something he wants “nothing to do with”. After the fateful meeting, he laments, “I fear the world’s end is near, humans have lost confidence.” This is the pivotal moment that brings Miyazaki out of retirement for the third time. “Hand drawing is the only answer, I won’t run away from in anymore.” He emerges with a handwritten plan for another feature, one he didn’t think he had in him, and it would be entirely hand drawn: The Boy and the Heron (2023).

Kiki’s Delivery Service demonstrates this same cycle, one that is never ending for Miyazaki, of honing your skills, losing the magic, and then finding it again by rediscovering your inspiration.

If you haven’t seen Kiki’s Delivery Service yet, please note there are spoilers beyond this point!

Kiki Flies the Coop

The opening sequence of Kiki’s Delivery Service introduces our protagonist, a young witch named Kiki, with her head in the trademark Ghibli Clouds. She dreams of leaving her bucolic hometown to go abroad for a year, customary for a young witch in training, and she suddenly decides that tonight is the perfect night to leave. Kiki is eager to grow up and leave home, but she still asks her father to lift her up high2 like when she was little, marking her last moments of childhood. Her mother worries that she’s not ready to leave home just yet, but Kiki flies the coop anyway (after hitting a few trees).

Kiki departs under the full moon and perfect conditions. The scene is euphoric, it’s the teenage witch equivalent of driving alone for the first time with the windows down and the music blasting— a celebration of freedom, the optimism of young adulthood. She then encounters another young witch who is further along in her training, specializing in telling fortunes of love. She asks Kiki what her specialty is, to which Kiki replies “I haven’t made up my mind yet.” Newly insecure, with no destination in mind and undeclared major, she flies straight into a thunderstorm.

The Disenchantment of Adulthood

After a rocky landing in a bustling seaside city, Kiki finds that adulthood isn’t what she imagined. Groceries are expensive! While eager to live independently as an adult, she’s reminded in many ways that she is still a child. The people in the city gives her a lukewarm reception, she has trouble finding a place to stay, and she feels unmoored after leaving the safety of her home.

Kiki accidentally starts her delivery service when she returns a pacifier to a bakery customer that’s walked too far away, using her magic for a random act of kindness. Osono, the bakery owner, offers her room and board. Flying is the only skill she has, and since she has to become self sufficient, she turns it into her specialty. Kiki turns her magic into her job.

To find one’s purpose, or passion, is a lifelong endeavor that we’re often expected to figure out when we’re teenagers. Adults bombard us with adages like, “do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life.” You like writing, so you major in English and get a job at an ad agency. You like drawing so you find work as a graphic designer. Cycles of creativity don’t always align with a 9-5 schedule. What happens when you turn your passion into a job you do for others, rather than something you do for yourself?

Burnout

Other children her age aren’t working, and Kiki finds herself quite isolated. After working hard, flying through another storm, dealing with a rude customer, and missing a social engagement, Kiki gets sick. She later finds she’s unable to fly, and she’s lost her magic. Dismayed, she falls into a depression. Magic is the source of her livelihood, it powers her flying. What will she do now?

Ursula, a new friend and a painter who lives outside the city visits Kiki, and upon finding that she’s lost her magic, invites her to an impromptu artist’s retreat at her house: an opportunity to recharge in nature. It’s in this rustic cabin in the woods that the thesis of the film is presented, in a conversation between two artists: Ursula, an established artist who’s figured out how to turn her magic into her livelihood, and Kiki, a young “artist,” still trying to harness her talents.

*The following is a transcript of the Japanese subtitles for these scenes, the English dub (produced by Disney for release in the US in 1997) varies slightly.

URSULA: Magic and painting are a lot alike. You know, a lot

of times, I just can't paint.

KIKI: Really? When that happens, what do you do?

[...]

Before, I could fly without giving it a thought.

But now, I don't know how I did it.

URSULA: When that happens, all one can do is struggle through

it. I draw and draw, and keep drawing.

KIKI: But then, if I can't fly...

URSULA: Then I stop drawing. I take walks, look at the

scenery, take naps, do nothing. Then after a while,

all of a sudden I get the urge to draw again.

KIKI: I wonder if that will happen?

URSULA: It will.Hayao Miyazaki wrote the screenplay for this adaptation, and the conversation between these two characters might be Miyazaki’s internal monologue, talking himself through his regular periods art block or burnout. “That was my last feature,” he’ll say, only to return as soon as he’s found inspiration for another.

The Old Fashioned Way

In Kiki’s world, magic powers, like traditions, are passed down from one generation to another. We all seek to carve out our own place in the world when we’re young, Kiki does. When she first leaves home, she hopes to do it on the broom she made herself, but at Jiji’s (her cat’s) insistence, leaves on her mother’s trusted broom. She also longs to wear the fashionable clothes the other girls in the city wear so she can fit in in the modern city, feeling inadequate and behind the times in the traditional witch garb her mother gave her.

Miyazaki’s fear of losing the old ways of making animation magic is deep seated. In the opening scenes of the film, when we first meet Kiki’s mother, she laments that some magical traditions, like her medicine-making, could become a lost art due to the changing times.

DORA: I remember well the day you came to this town. A tiny,

13-year-old girl riding on a broom, dropping out of the

sky. Eyes sparkling, a bit saucy...

KOKIRI: But that child [Kiki], all she's mastered is flying. And

there'll be no one to carry on my medicine-making.

DORA: It's the fault of the times. Everything's changing.

But for me and my rheumatism, your medicine works the

best.Unbeknownst to her mother, once she’s on her own, Kiki is surprisingly rigid with her small-town, old school ways, especially when she meets Tombo, a young boy from the city:

When Kiki arrives at a new customer’s home to pick up a delivery, a pie to be baked, and the modern oven isn’t working, she builds a fire in the wood-fired oven, carrying the knowledge from the generations before her.

In the film’s dramatic climax, Kiki gets her powers back in order to save Tombo from a crashing dirigible— a man-made, mechanical flying machine. If Miyazaki’s feelings toward new technologies were not made clear before, this is certainly the vehicle that makes it apparent. Kiki’s inspiration is up to interpretation, it could be kindness, it could be love, but she gets her powers back when she finds a really good reason to use them, a new inspiration that forces her to find them within herself. In the epilogue, Kiki flies on her broomstick alongside Tombo’s man-powered flying machine, so maybe Miyazaki is not entirely averse to new technologies.

AI is not Magic ✨

The reason a film about a teenage witch losing her powers is so relatable is because Miyazaki is able to beautifully capture a deeply human trait: burning out. Humans are not machines, we get tired, we run out of ideas. Hand drawn animation is labor intensive, and you have to have passion in order to create something magical.

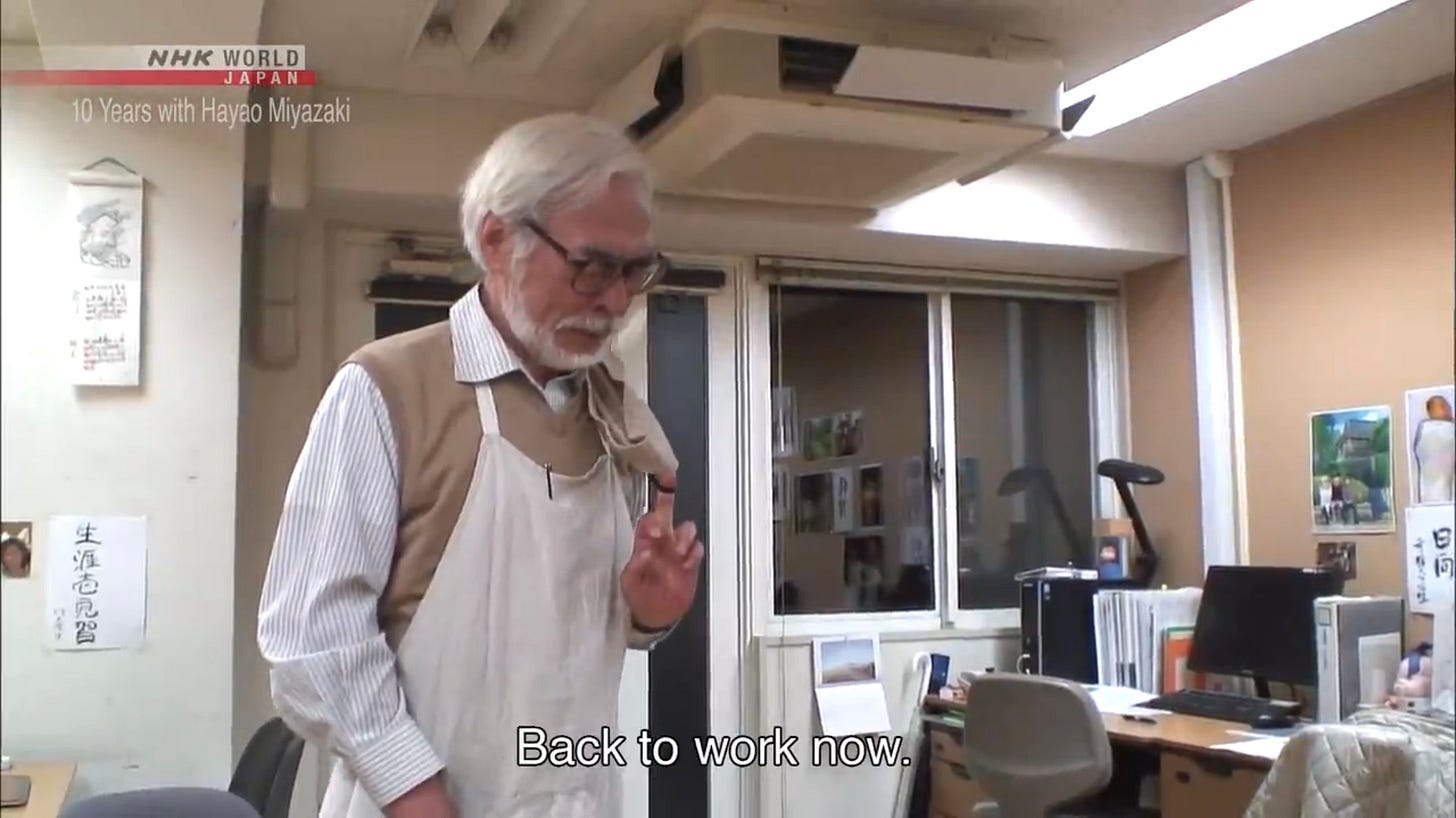

Making art is not supposed to be easy. In the 10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki docuseries, we watch Miyazaki struggle with writing and drawing Ponyo (2009). He scratches his head in frustration and does his anxious leg bounce, “the filmmaking has begun,” he remarks. It’s all part of the process.

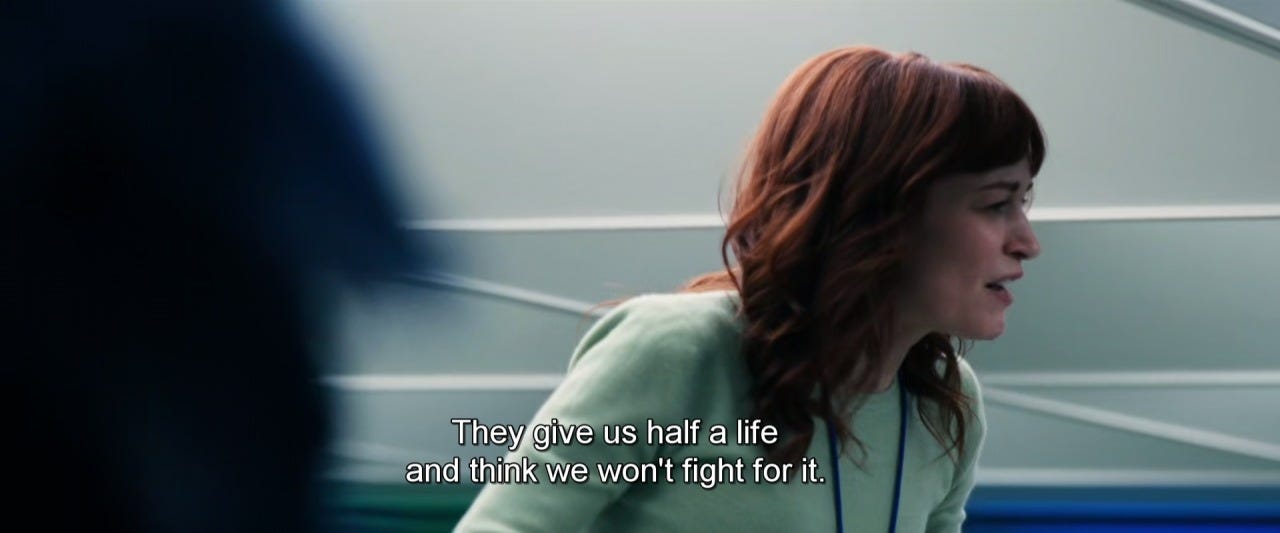

If you’ve watched Severance, skipping “the hard parts” of life is like slicing your brain in half. Periods of exhaustion, creative burnout, having a gap between your skill and what you want to create, or in Mark Scout’s3 case, grief, are a part of the human experience. Suffering is not a requirement for making art, but you should be feeling something, because you should be involved in the actual process making it. When Miyazaki talks about intent in relation to animation, and how he can achieve this more easily by hand-drawing, he’s talking about passion, motivation, the magic that only a human can infuse into their craft. What is the “intent” of using AI to generate art? To eliminate the “hard part”? The process of creating something? The process is what makes art!

Because Studio Ghibli creates such beautiful imagery, the aesthetic is often divorced from the meaning of the films, films whose themes are typically pacificism, environmentalism, and self-actualization. The Ghibli AI trend has made it so that the studio’s signature style can be co-opted at blinding speed, used to further agendas and waste natural resources in a way Miyazaki would never agree to.

In Spirited Away (2001), a character named No Face consumes other spirits in the bath house, using the voice of one, the hair of another, eventually becoming a monster, yet garnering adulation for throwing fool’s gold around. This is what AI art reminds me of. A bloated mess of stolen spirits, consuming everything in its path, puking out a grey sludge and wearing a mask to hide that it has no personality.

It seems like almost every website and app I use taunts me with the AI✨ sparkle emoji4, a symbol that has also been divorced from its old meaning. I used to use it to mean “magic,” now it means the opposite.

Studio Ghibli has yet to make an official statement on how their art has been used, but as ever, there are rumors that Miyazaki is still working, despite declaring that The Boy and the Heron was his last feature. I think he has to believe each feature is his last, so he can work like his magic is going to run out. Kiki’s magic comes back at the end of the movie. Cycles of creativity carry on for us humans. Spring will always return after the cold winter, and maybe Hayao Miyazaki will too.

[usually] lol

Helping her fly! 🥹

This is a Severance character, in case you don’t watch Severance. Severance.

Thank you for such an insightful essay, Dan. Kiki’s Delivery Service is my most favourite movie from Ghibli Studio. My son and I watch it more often. I've also written a brief note on Kiki's Delivery Service. If you ever wish to read, do let me know. I'll message it to you.

Keep writing.

Keep going.

Love love love this. Now I'm craving a rewatch. The cycle of creativity and burnout really makes sense for why Miyazaki always "retires" and then feels the need to create more. That conversation between Ursula and Kiki comparing painting to magic hits me just right. Great article and comparison to Miyazaki's creative process--I also need to watch that documentary!

(Also how dare they co-opt the sparkle emoji, that's one of my favs!!)